An interview with Remote Sensing expert Krista West

November 28th 2020. Melissa SterryKrista West has applied her remote sensing data analysis skills to support metropolitan and wildland fire departments during some of the largest California fire complexes on record. Having worked as an Intelligence Specialist and Instructor of Geosciences for the U.S. Air Force Academy, and with geospatial software company Intterra, she is pursuing a PhD with the San Diego State University / University of California, Santa Barbara Joint Doctoral Program. Here she shares her thoughts on how remote sensing technologies can help communities live with wildfire…

MS: Working with an array of remote sensing technologies, describe those you typically use day-to-day.

KW: I utilize optical multispectral data for the majority of my research, which is focused on wildland fire-prone Southern California ecoregions. The sensor data with which I currently work the most is Landsat; this joint NASA/U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) program has the longest continuous satellite data acquisition record and, since one of my research objectives is to evaluate land cover change and trends over time, Landsat provides me with the opportunity to analyze over 35 years’ worth of data. However, as Landsat’s 30-meter pixels are a bit coarse, I complement the data with airborne data sources, such as the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP). I use and classify NAIP data, which have 0.6-meter pixels, as my reference data. This way I can compare the Landsat and NAIP data outputs to determine whether I actually receive the land cover results I expect based on the methods I use.

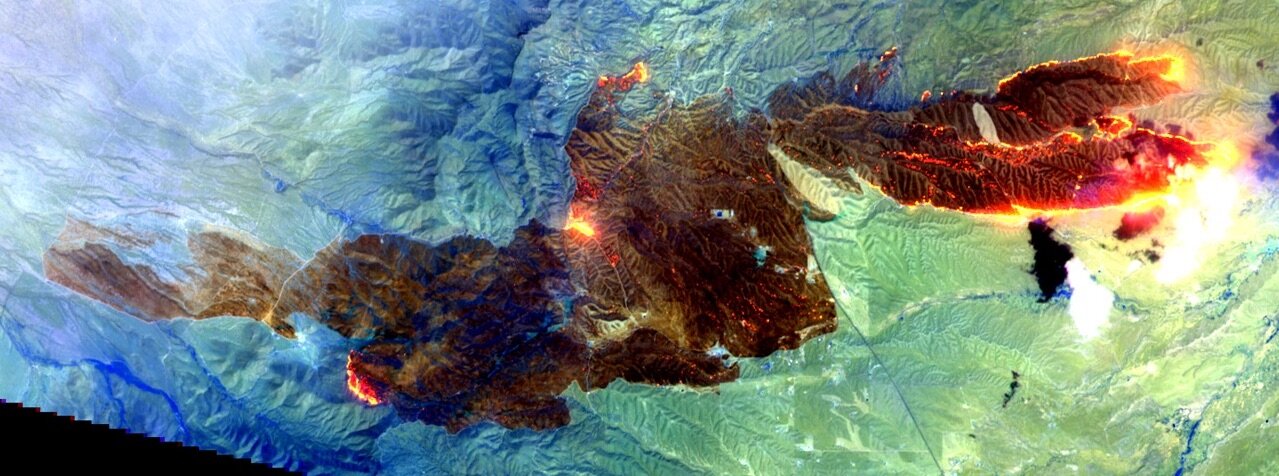

When looking at active wildland fire incidents, I utilize sensors with higher temporal and/or spectral resolutions. I appreciate Planet sensors’ almost-daily revisit time and I particularly enjoy working with Sentinel-2’s shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands, which allow me to “see” further in the electromagnetic spectrum than we can with our own eyes.

MS. Describe some of the ways in which your analyses of the data these technologies capture has enabled you to support fire crews and other emergency services during metropolitan and wildland fire events.

KW: While working with Intterra, I helped acquire the most recent spaceborne and airborne image datasets to share with our customers. Access to these data allowed firefighters in the field to see the impacted area from a very high level view and also on their constantly updating Intterra map app.

Unfortunately, one downside of utilizing remotely sensed imagery for an active incident is that, no matter how quickly you can obtain data, it’s usually not soon enough. An active fire front can move so fast that anything but real-time data is generally not useful for wildland firefighters. Remotely sensed data are extremely useful for looking at landscapes before and after an emergency, but we’re still working toward a solution that benefits boots on the ground in the middle of a fire fight.

With my current research objectives, my focus is on identifying areas with herbaceous growth form cover. Over time, many native Southern California shrub ecoregions have been replaced by mostly invasive grasses and forbs, originally introduced by European settlers. This vegetation is considered to be a “flashy” fuel – when dry, and particularly during an extreme wind event, it ignites easily and spreads flames faster than native herbaceous vegetation and shrubs. Using Landsat, I am determining fractional cover values of land cover types, and identifying the locations with herbaceous vegetation. The output can be used by firefighters before the fire season to identify areas that may be at a higher risk in the event of an ignition.

MS: Having trained and worked in remote sensing analysis for over a decade, what do you think to be the most pivotal software, hardware, and other innovations to have impacted the sector in that time and why?

KW: It has certainly been exciting to watch data innovations and the impressive magnitude of improvements in just the last decade. Of note is the incredible amount of available data right now – both due to open source options and also because of the number of new sensors and platforms that have been manufactured and launched/flown.

Companies who created cubesats, like Planet, have launched hundreds of their sensors into orbit so that we now have almost daily revisits of the same geographic location and at the fairly high spatial resolution of a few meters. Maxar’s WorldView-3, the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2, and NASA/USGS’s Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) sensors have bands in the SWIR part of the electromagnetic spectrum (and Landsat 8 OLI also has bands in the thermal infrared (TIR)), which is a game changer for those monitoring wildland fire incidents. The designs of hyperspectral sensors have significantly improved, and radar and Light Detection And Ranging (LiDAR) technologies are also becoming more affordable and available. There are also new(er) free software options with higher computing power (like QGIS). I’m currently learning how to use Google Earth Engine (GEE), which has already saved me a significant amount of preprocessing time. L3 Harris Geospatial’s ENVI+IDL, Hexagon Geospatial’s ERDAS IMAGINE, and esri’s ArcGIS products have also stepped up their game – the tools work well with many different data types and support all sorts of users, from academic researchers to emergency responders.

MS: Thinking to the years ahead, which emerging remote sensing technologies do you think will have the biggest impact to your work assisting emergency services and why?

KW: I’m really excited about Planet’s PlanetScope SuperDoves, which have eight spectral bands (as opposed to the original four bands of PlanetScope Doves). Not only will we still see the high-revisit rate combined with good spatial resolution, but now we’ll have higher spectral resolution too, which will allow us to better differentiate between materials on the Earth’s surface. Although Planet’s SuperDoves will not be “staring” at the same spot 24/7 (due to their sun synchronous orbits), their upgraded tech will make them more useful and usable for emergency response efforts.

Currently, the remotely sensed technology that has been most useful for boots on the ground includes images and video acquired by airborne resources, such as Fire Integrated Real-Time Intelligence System (FIRIS), Colorado Division of Fire Prevention & Control Multi-Mission Aircraft (MMA), and the National Guard’s MQ-9 Reaper and RC-26. I am eager to see more fire departments acquire their own sensors that can be attached to apparatus to help them during active incidents. Great strides have been made to create smaller and more affordable sensor options. Use of this capability allows for real-time data gathering that can be efficiently utilized to monitor fire spread and help make operational and resourcing decisions.

MS: Casting your thoughts to artificial intelligence, to machine learning more generally, and to Big [Earth] Data, how do you think advancements in these fields may shape your work, and that of your remote sensing data peers by the year 2030?

I am intrigued by the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning, and Computer Vision algorithms to detect columns of wildland fire smoke immediately following ignition by stationary cameras, such as those included in the ALERTWildfire network. I’ve seen some groups working on this and think it’s a great idea because those images are constantly “staring” from a good vantage point and they update in near real-time. I would also be interested to see more fusion of data – vegetation/fuel, weather, topography, and imagery – to more accurately predict and simulate wildland fire movement; Technosylva is doing incredible work in this area. Similarly exciting is the work performed by Descartes Labs to detect wildland fires with AI analysis of satellite image data to detect smoke and/or a shift in TIR data showing hot spots.

MS: Thinking to biosensing, biocomputing, and other biotechnologies that are being integrated into environmental monitoring, which interest you most and why?

KW: These fields are a mystery to me, but I am eager to learn more. Perhaps I’m old school (or not thinking big enough when it comes to possible future technologies), but I still find that I’m able to answer many of my research objectives with the data I can access now. One of the reasons I find remote sensing to be such an awesome field is that I can look at a snapshot of the Earth’s surface and learn a great deal about what’s happening – whether the vegetation is stressed, if the soil is moist or dry, etc. – all by using infrared bands.

MS: Technological advancements often manifest unintended consequences. Can you think of any ways in which remote sensing technologies that have been developed to help may be abused by they that wish to hinder?

KW: The most immediate example that comes to mind is the use of hobby drones during wildland fires. Unfortunately, #IfYouFlyWeCant and #NoDronesInFireZones trend on social media during fire incidents because, for whatever reason, people insist on flying their drones to capture images and videos of disasters. Please don’t interpret this to mean I am anti-drone; I am very impressed with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones and the usefulness of their data acquisition capabilities. However, I am continuously frustrated when I read that firefighting aircraft have to be grounded because of safety concerns associated with someone selfishly flying their own tool; in that time, countless lives and structures can be lost. I understand that some may be attempting to help, but I hope that all drone pilots will be responsible and focus on staying out of the way of emergency responders.

MS: Of the various platforms and apps where remote sensing data can be found, which three would you recommended to those interested in learning more about remote sensing?

KW: This is an excellent question because there are so many tools from which to choose. Here are free options that I recommend using to learn more about remote sensing:

(1) I highly recommend using the Sentinel Hub EO Browser (owned and operated by Sinergise) to learn more about remote sensing data and band visualization combinations. The EO Browser helps users discover data sources, shares details about data options, allows for users to visualize image selections, and also teaches users about true and false color composite images (depending on electromagnetic spectrum band combinations). The user interface is simple and intuitive.

(2) I am a huge fan of the Windy Forecast platform and app and, if you think maps and weather are neat, you’ll see why I like it. The Windy tool includes weather radar and satellite map overlays; air quality layers (which include fire intensity and PM2.5); and, if you select a point on the map, data from nearby weather stations and webcams (when available).

(3) As I become more comfortable with writing and editing scripts, I’m loving Google Earth Engine. It’s not as intuitive as EO Browser or Windy but, once you work through some of the tutorials, you’ll quickly learn what a powerful tool it can be. Many proficient coders, researchers, and educators share their scripts, which includes beginning to advanced remote sensing lab-type write-ups.

Bonus recommendation: To learn more about both wildland fire and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), I suggest the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) Fire Enterprise Geospatial Portal (EGP) (powered by Intterra). During fire season, this is the first tool I check every morning. Simply zoom in on your area of interest, use the left-side toolbar to pick and choose data layers, and then dive into the details about a specific fire incident.

MS: A champion of women fire scientists and technicians, which three have inspired you most and why?

KW:

(1) Dr. Sarah Robinson (U.S. Air Force Academy Assistant Professor of Geosciences)

During my one year at USAFA, I taught the Introductory and Advanced Remote Sensing courses developed by Dr. Sarah Robinson. She taught me about course and curriculum development, teaching techniques, and also helped me improve upon my own remote sensing skills. I learned so much more about the “why” of remote sensing research – she taught me to pay attention to the specifics associated with research objectives; how to determine the best data to use based on a sensor’s spatial, spectral, and temporal resolution; and the most efficient data processing and analysis techniques to utilize to answer my research questions. I don’t think I have ever met a more dedicated teacher, and she still inspires me to stay curious and pursue interesting topics.

(2) Kate Dargan (Intterra Co-Founder & Chairman of Board; member of the U.S. Geospatial Intelligence Foundation (USGIF) Board of Directors; retired State Fire Marshal for California)

It was an honor to work with Kate Dargan at Intterra, and I am so thankful that she and I continue to be in contact. She was among the first women to be hired by CAL FIRE and, after being promoted from firefighter to engineer to fire captain, she started doing remote sensing as an air attack officer. Kate was also the first woman to be promoted to California State Fire Marshal. She co-founded Intterra; she is extremely involved in public, elected, and non-profit organizations; and she serves on several boards of groups associated with wildland fire and public safety. I don’t often use the word “visionary” but, when you check Merriam-Webster, I think Kate’s name should be listed with the definition – she is inventive, imaginative, and an incredible leader. She is constantly making insightful connections between existing and proposed technologies and research, and inspires the members of every organization with whom she works to collaborate and fill knowledge gaps.

(3) Dr. Alexandra Syphard (Conservation Biology Institute Senior Research Scientist; San Diego State University Adjunct Professor, Geography; Diversity & Distributions Associate Editor)

Dr. Alexandra Syphard and I are currently working together on the Climate Science Alliance (CSA) Connecting Wildlands & Communities (CWC) project, and she is a fellow Team Fire member. When I first met her in Fall 2019, I had already read a number of her publications, and was honestly starstruck. She is a subject matter expert on the topics of ecological and social drivers and impacts of landscape change, vegetation dynamics and biodiversity, invasive species, and wildland fire risk to communities. It has been a pleasure to work with her, and I am in awe during every team meeting as I listen to her share results from her research; she is adamant about focusing on the results of the data and isn’t biased by research fads. I admire her work ethic and her passion for sharing and communicating science topics related to fire.

Although not a remote sensing or fire scientist, I would also like to acknowledge my first inspiration – my mother, Pamela Lee. She is an astronomical and astronautical artist and one of the first women to pursue this genre of fine art. Working in a male-dominated industry never stopped her, and she motivates me to pursue my passions and makes the fusion of science, technology, and art truly beautiful.

MS: Describe your PhD research and the difference you hope it may make to the field.

KW: My current research objectives include:

Use Landsat imagery for quantification of fractional herbaceous vegetation cover in Southern California, USA.

Develop a remote sensing approach for tracking herbaceous growth forms, compare it to existing metrics approaches, and apply that approach to over three decades’ worth of image data.

Determine the effect of herbaceous expansion on the Southern California fire regime, both in terms of ignition potential and the likelihood of uncontrolled spread.

In addition to adding to the research body of knowledge and filling gaps in the remote sensing community, I hope that my results will benefit first responders and policy makers. I am optimistic that my data can be used to more accurately identify areas with flashy fuels so that mitigation can be performed before there is an emergency.

MS: The year is 2030. What’s the worst-case West Coast US wildland fire scenario you visualise?

KW: We continue to build homes and structures further into the wildland-urban interface and intermix, but have taken zero steps toward wildland fire mitigation. Funding and budgets to emergency responders have been cut, which prevents them from having the staffing, number of departments, apparatus, public information officers, and fire marshals they need to ensure the communities have adequate education and resources in the event of an ignition. Climate continues along the current trajectory causing even drier fuels and soils, destructive insect infestations increase, and more extreme wind events and dry lightning roll through the landscape. Fires occur in the same locations so frequently that native flora and fauna have no opportunity to re-populate. People are tired of wildland fire-related news, so they give up on preparing for the possibility of an incident affecting them. Natural and human-caused wildland fires continue to ignite and burn the highly populated wildland-urban interface structures, displacing people (or worse).

MS: The year is 2030. What’s the best-case West Coast US wildland fire scenario you visualise?

KW: Ideally, we will have adequate resources and tools to determine the areas at the highest risk of a wildland fire (to include products I help create) that would affect humans and endangered flora and fauna, the ability to educate those communities, and the time and funding to pursue mitigation steps. Homeowners will harden their structures, clear brush within the proper radius, and replace flammable landscaping materials with something that can both withstand a fire event and prevent flying embers that will negatively affect neighbors. Fire science, and the benefits of prescribed and managed fires, will be regularly communicated to people. Policy and decision makers will operate closely with scientists to learn about results from the data, and work together to make informed decisions that protect lives and structures. Perhaps the Civilian Conservation Corps is reinstated to assist with country-wide mitigation, offering employment to those who have been hard hit and also an opportunity to assist with the protection and resilience of their communities. Constellations of cubesats with SWIR and TIR bands will image the entire Earth’s surface at once and, when combined with real-time weather and topographic data by AI, will provide critical life-saving wildland fire alerts, predict fire propagation paths, and recommend firefighting resource assignments.

Read more about Krista’s research here.

Images: [Top] Sawmill Fire, Arizona, April 25th 2017 using Sentinel-2A (ESA) False Colour (SWIR band combination); [Middle] Thomas Fire, California, December 12th 2017 using RapidEye (Planet Labs Inc. https://api.planet.com) False Colour (NIR, Red Edge, Red Band combination); and [Bottom] August Complex Fire, California, September 1st 2020 using Landsat 8 OLI (USGS) True Colour (Red, Green, Blue band combination). All processed in ENVI+IDL by Krista West.