Seasons Greetings

Biomimetic Baubles

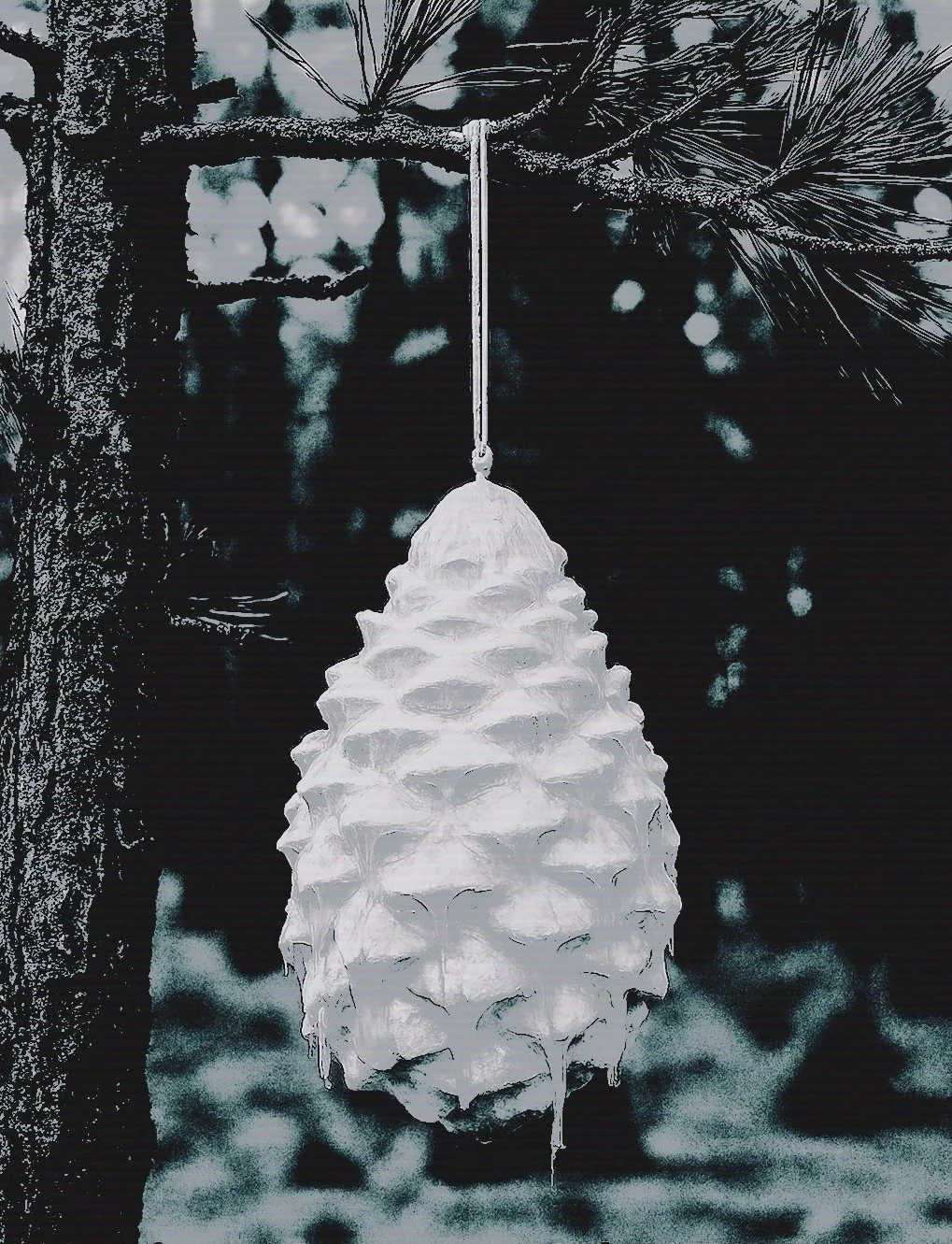

Pictured here, hanging from a tree like a bauble, the Pyri-CONE™ wildfire sensing concept was inspired by a serotinous cone collected during a walk through a pyrophilic forest in San Diego County nearly three decades ago. First described in Panarchistic Architecture (2018), the biomimetic device is triggered by heat and/or the chemical signals of wildfires and forms part of an ecosystem of bio-inspired technologies known as the ‘Biological Internet of Things’, or [B]IOT™. While many aspects of the [B]IOT™ remain the subject of ongoing research and development, some elements - such as the idea illustrated here - emerge from the migration of solutions found in other domains.

Integrating data from multiple sensing classes across land, air, and space, the purpose of the [B]IOT™ is to protect lives, properties, livelihoods, and pyrophilic ecosystems. Wildfire is construed not as foe, but as friend, because the pyrophytes that inspired both the Pyri-CONE™ - and the wider system of which it forms a part - have evolved to live with fire rather than without it. Panarchistic Architecture, and its sub-class Pyrophytic Architecture™, seek to reconcile human material and information systems with those of the non-human world. By syncing these domains so that they operate synergistically and in mutually beneficial ways, this approach integrates the many traits that have enabled plants, including pyrophytic conifers, not merely to survive wildfires, but to thrive with them.

More generally, the mimicry of pyrophytes and the ecological systems they form is a complex and demanding endeavour, involving research across multiple scientific domains and the wider STEM fields. For such approaches to be effective, however, design for living with wildfire must be as economically viable as it is ecologically synergistic, and must therefore hold appeal for the communities for whom it is intended. In vitro, Pyri-CONE™ could operate effectively at both surface and canopy height. In natura, however, the most effective configuration is suspension above ground level, whether from a branch, a beam, a telegraph pole, or similar structure.

In theory, the method of attachment could mimic that of a natural cone. In practice, a far simpler solution is sufficient: suspending the device from a cord. Affixing Pyri-CONE™ devices to trees in the manner of baubles evokes the idea of families and communities coming together to do just that, as part of a seasonal ritual akin to decorating a Christmas tree.

How humans engage with design is critical to its success or failure. Wildfire is already a highly contentious issue, and its management has been the subject of intense debate for many decades. In California, one key area of contention has been the centralisation of decision-making and, by extension, the systemic erosion of local communities’ ability to manage their own backyards. Ensuring that the very people proposals aim to protect are integral to their use and maintenance is therefore essential.

There are many ways in which systems such as the [B]IOT™ could be implemented and maintained by communities living in and beyond the wildland-urban-interface. The dominant narrative surrounding smart cities tends to emphasise centralised, hierarchical control systems, with government agencies and corporations positioned at the top. By contrast, an IoT modelled on an ecological system involves highly distributed decision-making. Equitable entanglement across diverse demographics requires not only technologies that can be understood and used by communities, but also cultural practices that are sufficiently appealing to be embraced across generations.

Viewed through this lens, the implementation of wildfire sensing could become an enjoyable community activity, involving participants both young and old. The act of hanging bio-inspired sensing devices on trees in and around a town within the wildland-urban-interface at a given time - such as the Winter Solstice - could incorporate storytelling practices that educate as well as entertain, echoing the pedagogical traditions found in historical fire cultures.

Historically, building resilience to wildfires in residential areas was a collective endeavour. Knowledge of fire ecology and broader environmental processes was informally passed down from childhood onwards. Citizens living in fire-prone regions were literate in fire behaviours, particularly as they manifested in their local environments. No single institution was responsible for teaching this knowledge, and no one individual exercised ultimate control. At a time when certain aspects of globalisation are faltering, and when economic instability increasingly places pressure on local and state firefighting resources and funding, hands-on engagement of the biomimetic bauble kind may be less fanciful than it initially appears.

As winter settles in, the Design for Wildfire school team and I wish you a wonderful Christmas and a festive season filled with warmth, love, reflection, and renewal.

Signing off for the season, Melissa.